Future shipping

The 2015 Paris Climate agreement did not address CO2 emissions from shipping. It was an agreement in which nation states made commitments to limit the global temperature increase to 2 degrees Celsius in this century with an ambition for 1.5 degrees. In 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted a strategy to align shipping with the Paris agreement.

There are more than 60,000 merchant ships trading internationally. If the shipping sector was a country, it would be the 6th highest emitter in the world, ranked between Germany and Japan. Shipping accounts for almost 3% of global CO2 emissions which continue to rise rapidly. Since ships have a long life span, about 28 years, their emissions are locked in for many years to come.

Maersk Line, headquartered in Denmark, is the world’s largest container shipping company by both fleet size and has a cargo capacity of over 700 ships. A P Moller – Maersk has identified failure to de-carbonise as the single greatest threat to its whole business. It has made de-carbonising the driving priority in every aspect of its operations. Accelerated action on de-carbonising in this decade is critical if catastrophic and irreversible climate impacts are to be avoided. Maersk plan to have the first net zero vessel operating commercially by 2023, and to reach net zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

It is a punt into the unknown. The fuels that will be used in these ships are still in development and not yet available in commercial quantities. Forward ship orders need to anticipate ships that will run without fossil fuels. Ship builders must now build ships that enable ‘fuel flexibility’. The two fuels that are closest to being ready to deploy are ammonia and methanol.

Maersk strongly supports a price on CO2 emissions in shipping to stimulate the market for new zero emission fuels which will be more expensive at first. They are not waiting on the IMO for regulation. Whereas some in the shipping industry see LNG as a transitional fuel, Maersk plans to leapfrog that stage altogether. They are driven by the urgency of the climate emergency.

The transition in shipping will be ‘global, broad and deep’, according to Lloyds.

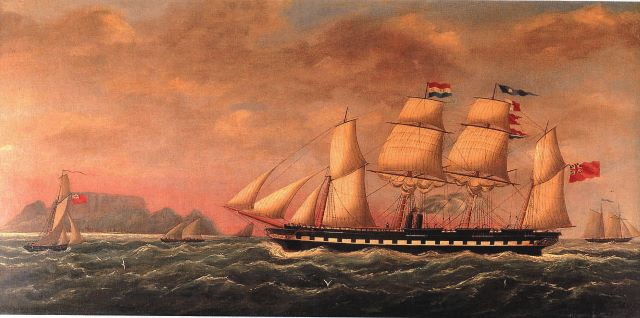

So it must have been when Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed the first Atlantic crossing steam ship, the SS Great Western. Later came the SS Great Britain which had many novel features – an iron, rather than a wooden hull, and a 12 knot 1000 hp steam engine -the biggest in the world at that time. The vessel was propelled by a screw propeller rather than a paddle wheel. The screw propeller stayed submerged all the time, and was less prone to damage.

The SS Great Britain made 36 trips to Australia between 1852 and 1875, using a combination of sail and steam. Her square sails were rigged to maximum advantage for the winds prevailing in the Atlantic and Pacific ocean. On her first voyage to Melbourne from Liverpool on 21st August 1852, she had 630 passengers, 143 crew and 1,400 tons of coal – ‘or thereabouts’ on board1. The coal was stored in every available space of the ship – in the bunkers, on deck, loose, under the forehold, in the platform and beams, in the trunk hatch, and further nooks and crannies.

In the vicinity of St Helena, the ship encountered severe weather and the captain was worried that there wouldn’t be enough coal to reach land. On September 16th, the ship’s log recorded “Every possible exertion being used to diminish the consumption, and the greatest anxiety felt”. The coal was used sparingly and the ship made its way to Cape Town safely and re-fuelled there.

But after that anxiety inducing first voyage, the SS Britain never again stopped on the voyage between Liverpool and Melbourne in a journey taking 60 days.

Sail continued to be a part of shipping until at least the turn of the century. Coal supplies were unreliable. In the early days, steam ships were not always as fast as sailing vessels. Coal took up a lot of space on board and many men were needed to shovel it. Sail was an important backup if coal was not available or if the ship’s engines failed.

When the SS Great Britain’s days in emigration were over, she reverted to being a sailing ship carrying coal – a bit like our Polly Woodside.

Fuel efficiency and slow steaming are also being actively pursued in the transition to zero carbon shipping. Profound changes are ahead for the shipping industry on which we all depend.

This week

18 May: The International Energy Agency released a major report on a roadmap to net-zero emissions in 2050.

18 May: The Australian Government announced plans for a $600m new gas fired power plant in the Hunter Valley

Notes

The SS Great Britain story

1Harvard/Australian citation1852 ‘ARRIVAL OF THE STEAMSHIP GREAT BRITAIN AT MELBOURNE.’, The Shipping Gazette and Sydney General Trade List (NSW : 1844 – 1860), 20 November, p. 323. , viewed 20 May 2021, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161035068

Bitty Muller

Fascinating post today Janet & delighted to see the shipping industry is taking action on carbon emissions.