Housing history in Port Melbourne

The (State Savings) Bank houses project was aimed at supporting low, but steady, income earners into home ownership. The houses were out of reach of the many people in Port Melbourne who were unemployed in the Depression years following the Waterfront Strike of 1928.

In the 1930s, pressure for action on housing ramped up.

Housing reformer, F Oswald Barnett, was a Methodist. He was an accountant by profession. He was shocked by what he saw of housing conditions in inner Melbourne.

Barnett was an effective advocate and skilled communicator. In many slide presentations well illustrated with photographs, slides and statistics, he brought the housing conditions in the inner city to the attention of decision makers and the press. He organised a tour of the ‘slums’, going down narrow lanes where politicians had to leave their cars, to experience conditions directly. The pressure was on. Premier Albert Dunstan appointed the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board in September 1936. It was chaired by MLC Henry Pye with Barnett as deputy. The Board conducted extensive on the ground surveys of more than 7,000 houses within 5 miles of the city centre.

The poorer quality housing was generally located in lanes and rights of way off main streets, as illustrated in this photograph.

Many of the dwellings were ‘falling to pieces owing to neglect, decay and old age’. The investigators classified the dwellings into slum pockets, congested areas, blighted areas and mixed areas.

Incidentally, they found that conditions in Port Melbourne were not as ‘acute’ as elsewhere with 464 houses examined in Port, compared to 1,117 in South Melbourne.

.

The housing reformers looked on these places and the people who lived there from an outsider’s, and very moralistic, perspective. Poor housing and ‘degeneracy’ went hand in hand.

Even though the houses surveyed were in extremely poor condition, since housing was scarce, rents were disproportionately high. The authors noted that the burden fell most heavily on those least able to afford it who were ‘shamefully exploited’ by their landlords.

In what we would now call ‘a name and shame’ exercise, the report listed all the landlords who owned the dwellings examined in the survey.

The authors recognised that there would always be people who could not afford to pay market rent, or afford their own homes.

A central recommendation of their report was the necessity for a central housing authority.

The Housing Commission of Victoria was set up under legislation passed in 1938.

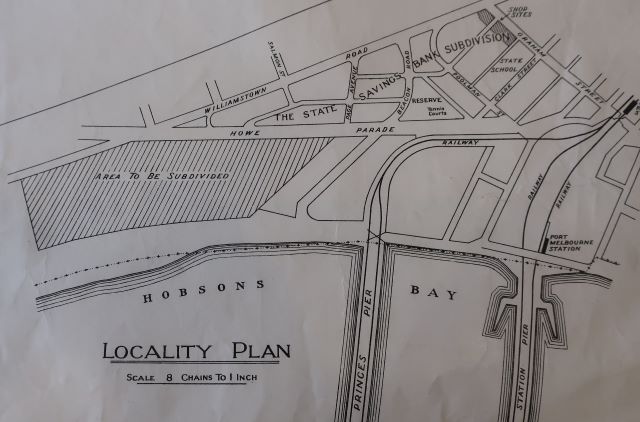

Those vacant lands at Fishermans Bend were the perfect location for the Housing Commission’s first large scale experiment in building housing for rental.

A competition was held for the layout of the estate which was won by Saxil Tuxen. Open space was central to the design.

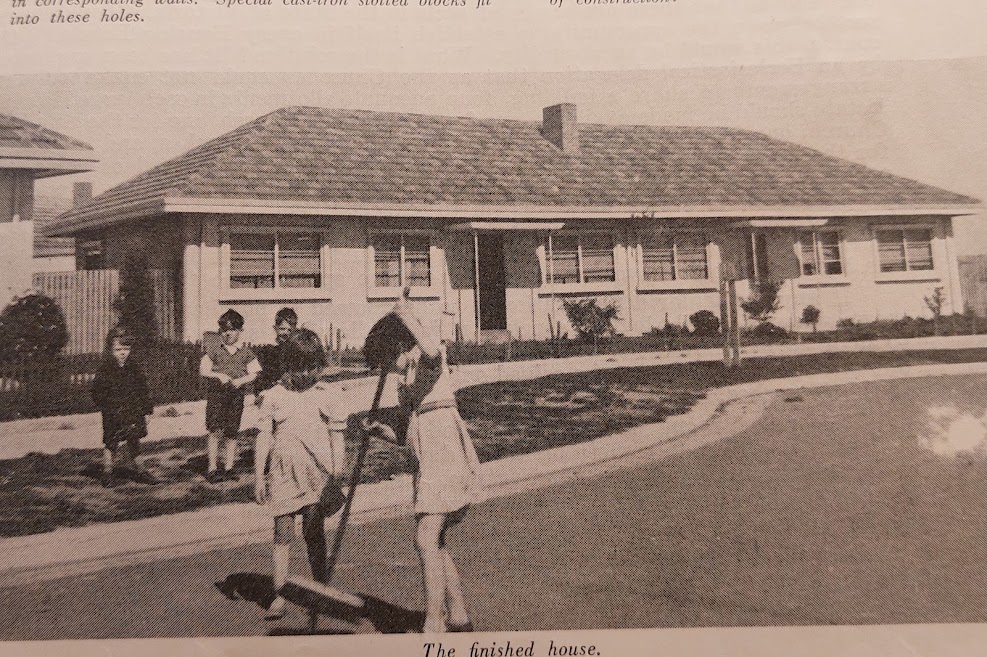

The houses were plain and modest but they had kitchens and bathrooms inside. The emphasis was on creating housing at scale using, for the first time, pre-fabricated concrete panels manufactured at Holmesglen. A range of community facilities were planned but not built at the time. People were relocated from other suburbs, such as Montague, to take up houses on the estate.

The estate, labelled clearly Fishermans Bend on the plans, was divided from the Garden City bank houses by Howe Parade.

In June, the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) released Towards an Australian Housing and Homelessness Strategy: understanding national approaches in contemporary policy.

The report’s leading recommendation is that Australia should have a Housing and Homelessness Strategy with a mission:

everyone in Australia has adequate housing.

The report notes the complexity and fragmentation of housing policy, the challenge of inter-governmental cooperation and suggests approaches to addressing these problems. Building a constituency of support for the mission and involving all players in the creation of the strategy are also vitally important.

The report says that the Strategy should have a statutory basis, enshrining the right to adequate housing, nominating Housing Australia as the lead agency, and establishing regulatory and accountability agencies.

The urgency of that word ‘mission’ runs through the report’s recommendations. It echoes the words of Barnett and his co-authors in their 1944 publication ‘We must go on’.

‘We have to be visionary to the point of audacity.’

Sources

Read the key points of AHURI’s report here.

Towards an Australian Housing and Homelessness Strategy; understanding national approaches in contemporary policy. Report 401, Chris Martin, Julie Lawson, Vivienne Milligan, Chris Hartley, Hal Pawson, Jago Dodson 15 June 2023

We must go on F O Barnett, W O Burt, F Heath 1944

Report of the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board

Judy Stanton

Sadly such a repeated story