Steps towards a water sensitive Fishermans Bend

We, that is Melburnians, use 50 GL more water each year than the rainfall that is captured in water storages, according to Water Minister Harriet Shing1.

Fishermans Bend, in a phrase repeated so often that it has lost its impact, is intended to be the future home of 80,000 people as well as 80,000 workers.

Therefore, planning for the future of Fishermans Bend has to include planning for water in all its dimensions and manifestations – water supply, flooding and greening the landscape.

All this planning is outlined in the Fishermans Bend Water Sensitive Cities Strategy released in May 2022.

Responsibility for the implementation of actions in the strategy is assigned to Melbourne Water, agencies, developers and the Cities of Melbourne and Port Phillip.

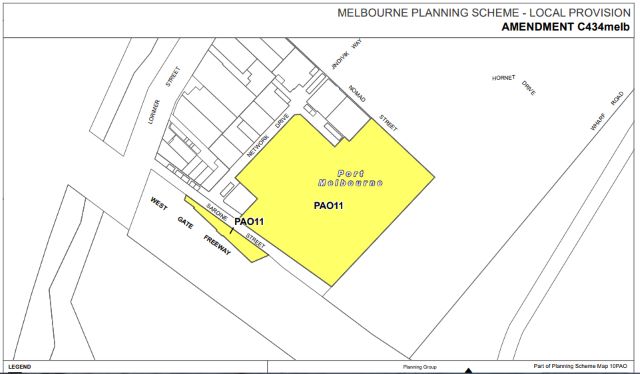

A water recycling plant is a signature project of the Strategy. South East Water has been planning towards the water recycling plant for several years. The project took a decisive step forward on 5 October when the Minister for Planning approved Planning amendment C434melb which placed a Public Acquisition Overlay on two sites in Sardine St. Sardine St is at the very end of Lorimer St and runs parallel to the Westgate Bridge.

The water recycling plant will mine water from the Hobsons Bay main sewer nearby and recycle it to Class A standard. The recycled water will be used in Fishermans Bend for all other purposes apart from drinking.

The plant is intended to be operational by 2030, and will be built in three stages.

An aspiration many people share is for Fishermans Bend to be ‘green’ – for public spaces that are cool and shaded, and where trees and plants thrive. Rain gardens have a role to play. Rain gardens hold storm water after rain. As the water filters through the rain garden it is cleaned by microbial action on plant roots. The City of Port Phillip has become quite a specialist in rain gardens which have multiple benefits – they narrow streets to make them safer for walkers and cyclists, introduce greenery, add to biodiversity, cool the landscape and assist in flood mitigation.

Rain gardens are not random assortments of materials but a highly ordered formula of materials and plants. The many layers that make up a rain garden can be seen in the one currently under construction in Bridge St, outside the Doctors’ surgery.

Drawing on Fishermans Bend’s association with innovation, the City of Melbourne ran an an Innovation Challenge. Applicants pitched their ideas to a panel. University of Melbourne engineering student, Amira Moshinsky, won the challenge.

Amira’s proposition was to explore whether recycled materials such as construction waste could be used as the medium in rain gardens, rather than using new materials (sand and gravel) each time. After doing preliminary testing at the University, Amira and her colleagues have brought the experiment to public view off the shared path on Turner St.

The results of the experiment have recently been updated on a publicly available dashboard. You can see how they’re going. While the Remix rain gardens have proved very successful in removing phosphorus they have been less successful at removing nitrogen to the standard required to meet storm water guidelines. However, Amira anticipates that the results for nitrogen will improve when the plants grow and their root systems develop. The plants are all healthy.

The findings of this experiment will inform the potential of using recycled materials in future rain gardens in Fishermans Bend and elsewhere.

A third strand of the strategy is using water more efficiently.

Brendan Condon has an office in Rocklea Drive in Fishermans Bend. He is concerned about food insecurity. He sees the potential for ‘cities as catchments, cities as food bowls’. With his business partner, Marc Noyce, he conducted an experiment to find out how much food they could grow on two standard size carparks using the Biofilta foodcube.

They developed the foodcube to make it as easy as possible for people to grow their own food, especially in small urban spaces. It is made of recycled food grade plastic (and is itself recyclable) and is highly water efficient. It uses a wicking system whereby plant roots draw water from a reservoir at the base of the cube.

In 2019, these two car parks grew 467.8 kgs of fresh produce, more than the annual fresh vegetable requirement per person recommended by the World Health Organisation. The abundant regular harvest is donated to food charity OzHarvest Melbourne to be distributed to people in need.

1 The Fifth Estate 16 November 2023

More

Fishermans Water Sensitive Cities Strategy (May 2022)

Previous posts on wetlands, rain gardens and the foodcube

Big on solutions: an interview with Brendan Condon

Leave a Reply